The Colossal Odyssey of Greek and Cretan Sculpture: From Antiquity to Today

The island of Crete and the Greek mainland have been the birthplace of numerous artistic achievements, with sculpture being one of the most enduring. Spanning thousands of years, Greek and Cretan sculpture captures the essence of human emotion, the nobility of form, and the sacred in the ordinary. This article takes you on a journey through the ages, exploring how sculpture has evolved in this region, with a particular focus on Crete.

Minoan Period: The Dawning of Cretan Sculpture

The Minoan civilization, flourishing around 2000-1450 BCE, offers some of the earliest instances of sculpture in Crete. Intriguingly, the Minoans preferred smaller forms, such as terracotta figurines and miniature ivory sculptures, often depicting the human condition with exaggerated features like wide hips or bulging eyes. While not monumental in size, these pieces hold monumental significance. They tell us about Minoan religious practices, daily life, and even their fashion sense.

Key Artifacts:

- The Snake Goddess: This small faience figurine portrays a woman holding snakes in either hand, signifying her power and perhaps her divinity.

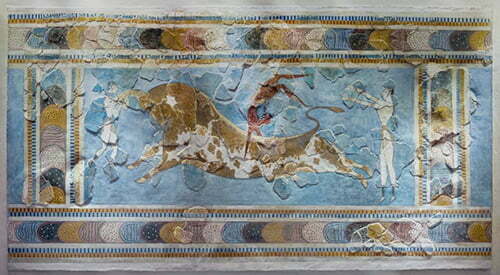

- The Bull-Leaping Fresco: While not a sculpture, this iconic fresco demonstrates the Minoans’ high regard for the form and movement, which influenced later Cretan and Greek sculptural traditions.

Classical Greek Period: The Idealization of the Human Form

The Classical Greek period (480–323 BCE) brought a revolutionary shift in the portrayal of the human form. Sculptors like Phidias and Praxiteles moved away from rigid, formulaic styles and embraced more naturalistic approaches.

Key Sculptures:

- The Parthenon Marbles: Carved under the supervision of Phidias, these marbles adorned the Parthenon temple and represent the epitome of the classical ideal.

- Hermes and the Infant Dionysus: Credited to Praxiteles, this sculpture exemplifies the new emphasis on grace and fluidity of form.

Hellenistic Period: The Drama of Emotion Expanded

The Hellenistic period represents a remarkable epoch in the timeline of Greek and Cretan sculpture, offering a dramatic departure from the balanced, idealized forms of the Classical Age. From the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE to the rise of the Roman Empire in 31 BCE, this era enriched the vocabulary of sculpture by incorporating deep emotional resonance, lifelike details, and the stark individuality of subjects.

Transformation from the Classical Aesthetic

If the Classical period was about the ‘ideal form,’ the Hellenistic period was about the ‘real form.’ The era introduced a different language of expression charged with psychological depth. While classical sculptors like Phidias and Praxiteles aimed for an idealized, almost god-like portrayal of human beauty, Hellenistic artists were more interested in the reality of human emotion and the drama of human experience. These artists explored the nuances of human psychology, joy, sorrow, ageing, and even deformity.

Subject Matter and Themes

The Hellenistic period saw a diversification in the subject matter. Alongside the deities and heroes of old, everyday people and the elderly appeared as subjects, children, animals, and mythological figures caught in moments of intense emotion or action. This period also saw the development of ‘genre sculptures,’ ordinary people captured in everyday acts—a fisherman, a shepherd, or even a drunk woman.

Innovations in Technique and Material

Technologically, the Hellenistic era also introduced innovations like drilling techniques that created deeper folds and hollowed eyes, making sculptures appear strikingly realistic. Artists employed bronze casting, a medium that allowed for more dynamic poses since bronze has a higher tensile strength than marble. While many of these bronze sculptures have not survived, the few that have been celebrated as masterpieces.

Key Sculptures

- The Dying Gaul: This sculpture, initially crafted in bronze, portrays a wounded Galatian soldier in his final moments. The realism, from the contorted facial expression to the tension in his muscles, embodies the Hellenistic trait of emotional drama.

- The Barberini Faun: Depicting a drunken satyr, this sculpture reveals its sense of abandonment and ecstasy. The pose is dynamic, with limbs sprawled in different directions, capturing an essence of uninhibited emotion.

- Venus de Milo: Though often considered a symbol of classical beauty, the sculpture’s somewhat enigmatic expression and fluid form align more closely with Hellenistic sensibilities.

- The Boxer at Rest: This sculpture showcases an aged, battered boxer sitting in quiet contemplation, his face scarred and his posture slumped. The work is incredibly detailed: even the cauliflower ears and broken nose are visible. This raw, unglamorous portrayal was a novelty brought by the Hellenistic age.

Influence on Later Art

The Hellenistic influence was so profound that it endured through the Roman era and into the Renaissance. The sense of ‘realism’ and the focus on ‘individual expression’ were elements that later artists would find significantly inspiring. Works of this period were aesthetically appealing and profoundly thought-provoking, posing questions about human vulnerability, courage, and the complexity of emotions.

The Cretan Perspective

While Crete, during the Hellenistic period, was under the influence of the broader Hellenistic world, it was far from a passive receptor. Local artists often synthesized the prevalent styles with indigenous traditions. Cretan cities like Knossos, Phaistos, and Kydonia produced works of art that, though resonating with the emotional drama of the Hellenistic period, retained unique features, be it in the form of local gods and goddesses or the distinctively Cretan artistic motifs and materials.

Conclusion on the Hellenistic Period

As an era, the Hellenistic period was a time of exploration, expansion, and expression. It took the foundations laid by the classical age and built upon them, adding layers of emotional complexity, technical brilliance, and thematic diversity. In doing so, it enriched the existing sculptural traditions and set the stage for the myriad artistic explorations that would follow in the subsequent millennia.

Through a deeper understanding of Hellenistic sculpture, we gain more than just an aesthetic appreciation; we get a visceral, intimate look at the human experience in all its complicated glory. In capturing life in such a profound way, the sculptors of the Hellenistic period bequeathed to us not just art but also an enduring exploration of humanity itself.

Byzantine and Medieval Periods: A Spiritual Focus

Following the decline of the Hellenistic period, the rise of Christianity marked a shift in the themes and styles of sculpture. The focus now was on religious icons and architectural elements, like the ornate capitals in churches throughout Crete.

Key Artifacts:

- Iconostasis Panels: Carved wooden panels separated the altar from the nave in Byzantine churches.

- Venetian Lion Statues: During Venetian rule, lion statues became common in Crete, symbolizing the republic’s influence.

Modern Era: The Rebirth of Cretan Sculpture

In modern times, Crete has witnessed a resurgence of interest in sculpture, drawing from its ancient heritage and current artistic trends. Artists like Nikos Kazantzakis have even incorporated sculptural elements in public spaces as a tribute to Cretan resilience.

Key Artifacts:

- Monuments to Resistance: Several modern sculptures in Crete commemorate the island’s resistance during WWII.

- Public Art Installations: In cities like Heraklion, you’ll find a blend of traditional and contemporary sculpture adorning public spaces.

Conclusion

Greek and Cretan sculpture is a tapestry woven with the threads of history, culture, and artistry. From the small but potent figurines of the Minoan era to the grandeur of classical Greek masterpieces, the portrayal of the human form has evolved in fascinating ways.

This journey through the ages reveals how these sculptural artefacts are not merely objects of aesthetic pleasure but also pivotal in our understanding of societal changes and human thought across millennia.

Modern Crete’s artists contribute to this rich legacy, crafting works honouring the past and exploring new frontiers in form and meaning. Each chisel strike and sculpted curve adds another layer to this enduring odyssey of artistic expression.

Table of Contents

Views: 89